Inner Workings of LLMs for Developers - Part 1

The world of Artificial Intelligence (AI) is evolving at an unprecedented pace, with new models, architectures, and protocols emerging almost daily. In this exciting, yet sometimes overwhelming, landscape, it’s easy for the foundational principles to get lost in the noise. As developers, we often find ourselves racing to keep up with the latest advancements, inadvertently creating gaps in our understanding of the underlying fundamentals.

But as experienced professionals, we know the immense value of a solid foundation. That’s why I decided to start this blog post series: to revisit and reinforce the core concepts of Large Language Models (LLMs) before you dive into the concepts such as Agentic AI, MCP, and A2A.

This series is crafted specifically for developers. My aim is not to delve into complex mathematics. While it’s crucial for researchers, it’s often not essential for developers to understand. Instead, I’ll focus on explaining the concepts using clear language and visuals to make complex ideas easy to understand.

Let’s begin.

One of the core challenges in the field of Natural Language Processing (NLP) has always been the translation of unstructured, ambiguous human language into a structured format that machine learning algorithms can understand. For example, take the word ‘crane’. In the sentence, ‘The crane landed by the water to catch a fish,’ it’s a bird. But in, ‘The construction crew used a crane to lift the steel beam,’ it’s a machine. We understand this difference instantly from the context, but teaching a machine to do the same is a major challenge in NLP.

Machine learning models, such as classifiers and clustering models, operate on numbers (mathematical operations) and not words. Though text has long been represented numerically using formats like ASCII or Unicode, it only tells the computer what character to display but does not capture any information about the meaning of the words, their relationships, or the context in which they exist. For instance, typing “cat” immediately converts it into binary representations of ASCII or Unicode values for ‘c’, ‘a’, and ‘t’. The problem is that these numbers are meaningless and arbitrary from a linguistic perspective.

Early 2000s

Bag of Words emerged as the first model in the early 2000s that attempted to solve this challenge, or at least some part of it.

It provides a simple but effective way to represent text data in a numerical format that computers can understand and process. The core idea is to treat a piece of text, whether a sentence, a document, or a whole corpus as an unordered collection (“bag”) of its words. The model scans the text and does two things:

- It disregards all grammar, context, and word order.

- It simply counts how many times each word appears.

To understand how the BoW model works, let’s walk through an example. Our goal is to create a numerical representation for the following three sentences, which will serve as our text corpus:

- The cat sat on the mat.

- The dog played in the yard.

- The cat and the dog are friends.

Step 1: Pre-processing

Pre-processing typically involves:

- Lowercasing: Converting all text to lowercase to ensure that “The” and “the” are treated as the same word.

- Removing Punctuation: Punctuation often carries grammatical or structural information rather than core semantic meaning, and its removal simplifies the overall sentence structure.

Step 2: Tokenization

Tokenization is the process of breaking down a sentence into individual units called tokens. While these tokens can be words or even sub-parts of words, for the purpose of this example, we will use a simple technique, splitting the sentence by its whitespaces to create a list of individual words.

Step 3: Create Vocabulary

A model vocabulary is created by retaining all the unique words across the three sentences. It’s common to sort this vocabulary alphabetically.

Step 4: Numerical Representation

This is the final step where we convert each sentence into a numerical representation known as a vector. For each word in the input sentence, we check if it exists in the dictionary. If it does, we increment its count.

Step 4 is repeated for each of the input sentences to obtain the vector representation. The final vector representation for all the inputs:

- The cat sat on the mat: [0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 2, 0]

- The dog played in the yard: [0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 2, 1]

- The cat and the dog are friends: [1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 2, 0]

This simple array of numbers is now a fully structured, mathematical object. We can compare it with other vectors, feed it into a machine learning classifier, and perform calculations on it to achieve specific goals.

Further reading: Datacamp has an excellent blog post that describes details of implementing Bag of Words using Python

Use Cases for the Bag-of-Words Model

The simplicity and efficiency of the BoW model make it highly effective for a variety of tasks, especially where the presence of certain keywords is more important than the sentence structure.

- Document Classification: This is one of the most common applications. BoW can classify documents into predefined categories. For example, it can sort news articles into topics like “sports,” “politics,” or “technology” based on the words they contain.

- Spam Filtering: Email services use BoW to identify spam. By creating a vocabulary of words commonly found in spam emails (e.g., “prize,” “free,” “winner”), the model can score incoming emails and filter out the unwanted ones.

- Sentiment Analysis: Businesses use BoW to gauge public opinion from reviews or social media posts. By counting the frequency of positive (“excellent,” “love,” “great”) and negative (“terrible,” “disappointed,” “poor”) words, a system can classify a piece of text as having a positive, negative, or neutral sentiment.

- Information Retrieval: Search engines can use the principles of BoW to find documents that are relevant to a user’s query by matching the words in the query with the words in the documents.

Challenges with BoW Model

Even though the BoW model is quite useful in several use cases, it has several limitations that prevent it from being used in more sophisticated language AI tasks.

- The BoW model does not have a notion of context or word order. The sentences “This movie was not good, it was terrible.” and “This movie was good, not terrible.” would have the exact same BoW representation, even though their meanings are completely different.

- The BoW model is essentially color-blind to the meaning of words. It can see and count the words themselves, but it has no idea what they represent or how they relate to each other. Consider these two sentences: “The price of the house is high” and “The cost of the house is elevated”. These sentences convey the exact same idea, but for the model, the words ‘price’ and ‘cost’ (or ‘high’ and ‘elevated’) would be treated as completely separate and unrelated words even though they mean the same in this context.

- Another challenge is sparsity. The model creates a vector that is the size of the entire vocabulary of the text corpus. In the example that we saw earlier, the vocabulary size is 12, so each vector representation is of size 12. Imagine a large dataset with a vocabulary size of 10,000. Since any given input only contains a small fraction of the total vocabulary, these vectors are mostly filled with zeros, a condition known as sparsity. Sparse vectors can be computationally inefficient and require large amounts of memory.

- The model can only represent words that were present in the vocabulary created from the training data. If it encounters a new word at a later stage, it has no way to represent it and will simply ignore it.

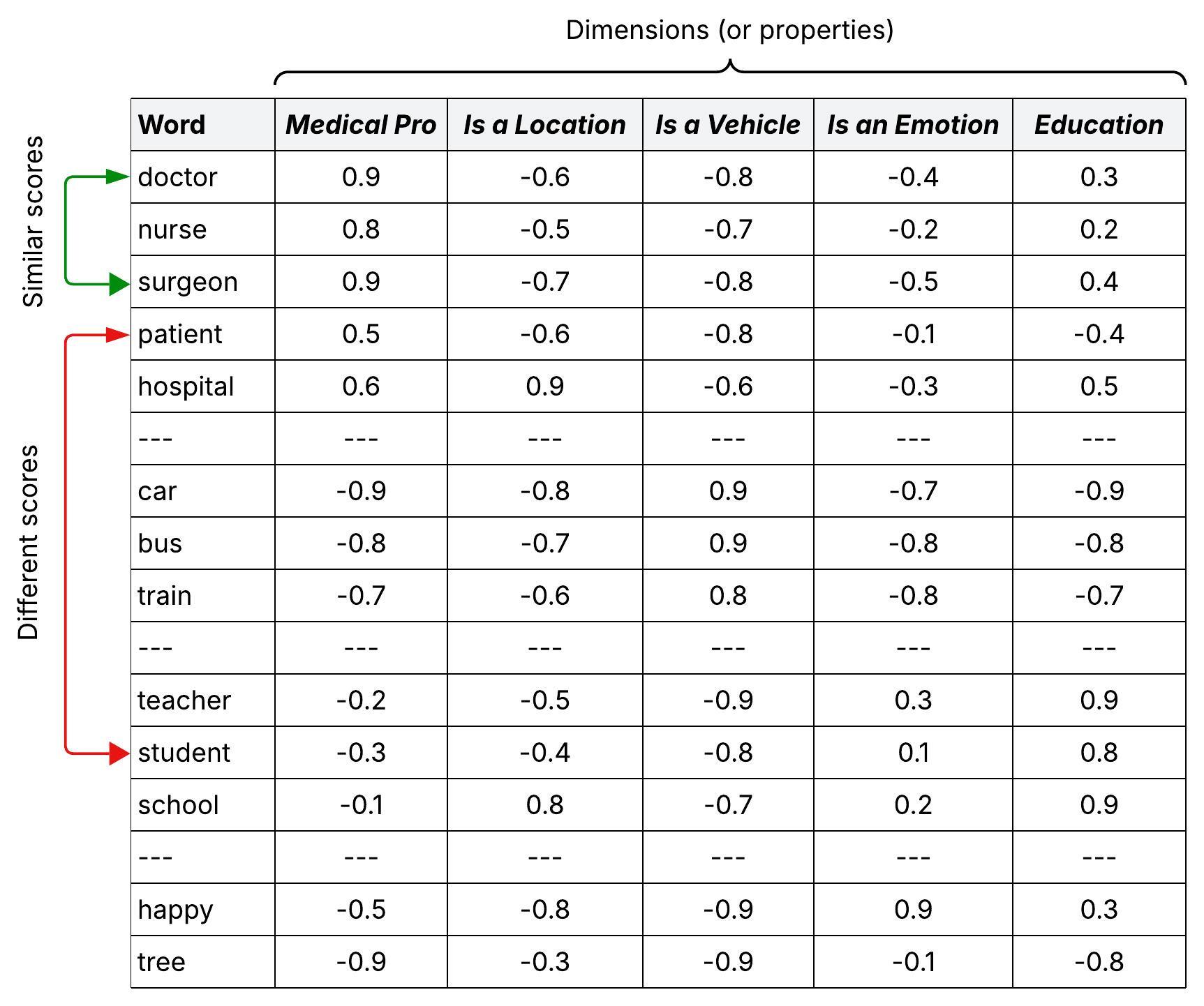

As we’ve seen, the Bag-of-Words model is blind to both context and meaning, treating words like ‘price’ and ‘cost’ as completely unrelated. So, how do we move from simply counting words to truly understanding them?

In Part 2 of this series, we’ll explore the revolutionary breakthrough that did just that: Word Embeddings and the groundbreaking Word2Vec model.

Leave a comment